Advocate explains the 'GE smell' and how workplace disease affected her friends

Sue James started working at the General Electric (GE) plant in Peterborough, ON, when she was 18. Now 65, she is starting to feel the effects of being exposed to dozens of toxic substances: "How much time do I have? I already have hearing loss, and I already have the beginnings of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). So my time is coming, and if I can make one bit of difference... "

James was born and raised in the city, and has lived there her entire life. Her father also worked at the plant for 36 years, from 1947 until 1983 when he retired.

He died at the age of 74 after initially being told he had COPD before being diagnosed with lung cancer. James’ mother put in a claim in 2007, and in 2009 the WSIB acknowledged he had been highly exposed to asbestos for most of his career in GE.

“I can't tell you what that acknowledgement meant to our family, and from that point on, I thought I need to help people so that they get that same acknowledgement.”

James retired in 2014, and is now an advocate for the former GE workers in Peterborough and a member of the Occupational Disease Reform Alliance (ODRA).

The ‘GE smell’

James started working at the plant in 1974 when she had just turned 18. Most of her friends and neighbours worked there as it was a major employer in the area.

“When I went to work there it felt – ironically – like I was going home,” she says. “Everything was familiar because the smells that my dad had on his clothing when he came home from work every day are imprinted in my mind.”

This smell that she is referring to is the “GE smell” – a chemical smell that most likely comes from the asbestos, a high number of known carcinogens and 3000 chemicals that were floating around in the air at the plant.

“I could walk blindfolded through the entire plant and just by the smells […] I could identify where I was,” says James.

After her retirement, James joined the advocacy group and together they worked on a retrospective exposure report. Part of the report was based on the testimonial of around 100 retired worked.

“We wanted to paint a larger picture of what it was actually like at the plant,” says James.

COS has approached GE for comment but has yet to receive an official response.

READ MORE: Ontario miners exposed to aluminum dust still fighting for justice

At the Peterborough workplace, James says everybody was exposed to the chemicals, meaning that everybody was at risk.

She describes paint booths, degreasers, welding, machining, hot ovens and overhead cranes – it was a constant movement of products throughout. Workers were constantly surrounded by fumes and dusts.

Among the most common products used were lead, asbestos, mercury, PCB’s, PVC’s and trichloroethylene to name only a few. Of these 3,000 chemicals, around 40 of them were known carcinogens.

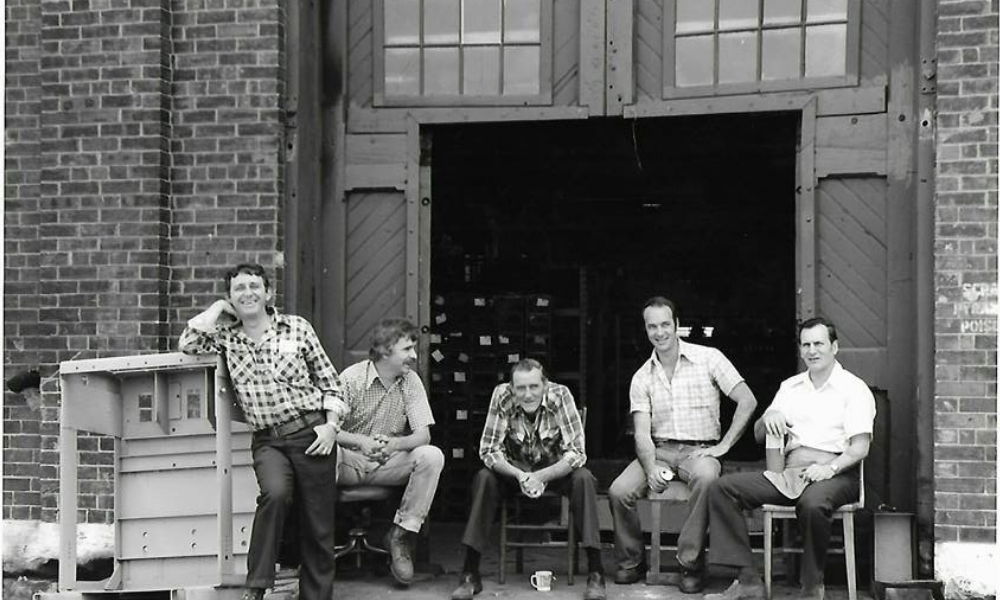

Employees Paul Thompson and Ted Millar, next to a large wire spool.

One large community

At the plant, the workers built motors of all shapes and sizes, from a quarter horse fractional motor up to large motors which would go into mining and icebreakers and hydro facilities.

James spent most of her career working in data collection – so part of the accounting and payroll piece.

“I had a lot of experience walking through the entire plant every day, multiple times a day. I met a lot of people – you know, my colleagues and I were just one large community,” she says. “The running joke in there was we never say anything about anybody until you knew who they were related to because most of the people were local.”

Around 1994, it was becoming evident that people were dying; they were contracting illnesses, mainly cancers.

Peterborough has a 40 per cent higher rate of mesothelioma compared to the provincial average (mesothelioma is a cancer caused by exposure to asbestos).

“I personally never connected the dots because I figured I was safe. [But] we have a lot of long latency illnesses coming out of that plant.”

The sheer number of people getting ill and dying was enough to spark concern among the local community. Despite this, compensation claims were being turned down, with exposures described as anecdotal.

Around 700 workers and their families filed claims, but thus far only a third have been compensated. In 2004 approximately 777 workers from GE and Ventra Plastics plants in Peterborough attended an intake clinic hosted by OHCOW and the CAW union (now UNIFOR) to document their exposures. Many workers never had the chance to file a claim or their claims were abandoned. Of those that were filed only a small portion of the claims were ever compensated.

Burden of proof

During her seven years fighting through this, James says that one thing she has noted is an inconsistent response to compensation claims. Some workers who died of the same lung cancer as her father had their claims turned down for example.

James says that in her experience denials are related to non-occupational factors (smoking, drinking) as well as age and gender. Rather than focusing on the multiple exposures these workers were exposed to on a daily basis with little to no protective equipment and poor ventilation.

The burden of proof is so high for those making claims that it can be hard to get a positive outcome. But, she says: “The body count is proof that something was wrong. We do not need scientific certainty when there’s logic and common sense.”

Another one of the struggles in this case was that GE was one of the biggest employers in the community, and some people may have been reluctant to raise the alarm for fear of losing their employment.

“It was a good place to work, but it was the people that made it. There was loyalty, we were proud of what we produced because GE was known worldwide. There was a sense of pride, but I don’t have that anymore.”

Did GE do anything to prevent workers from being exposed?

“No, nothing – and I can say that honestly,” says James, “because there was no ventilation. There was a lot of discussion on ventilation in the plating shops, the welding shops. But they were reluctant because that costs a lot of money. And so it was always profit over lives.”

Though there were some sporadic pushes for change, by and large nothing was done with regard to exposures.

“They did not even look at the patterns that were existing of all these people that were dying from cancers, heart diseases, neurological diseases,” she says.

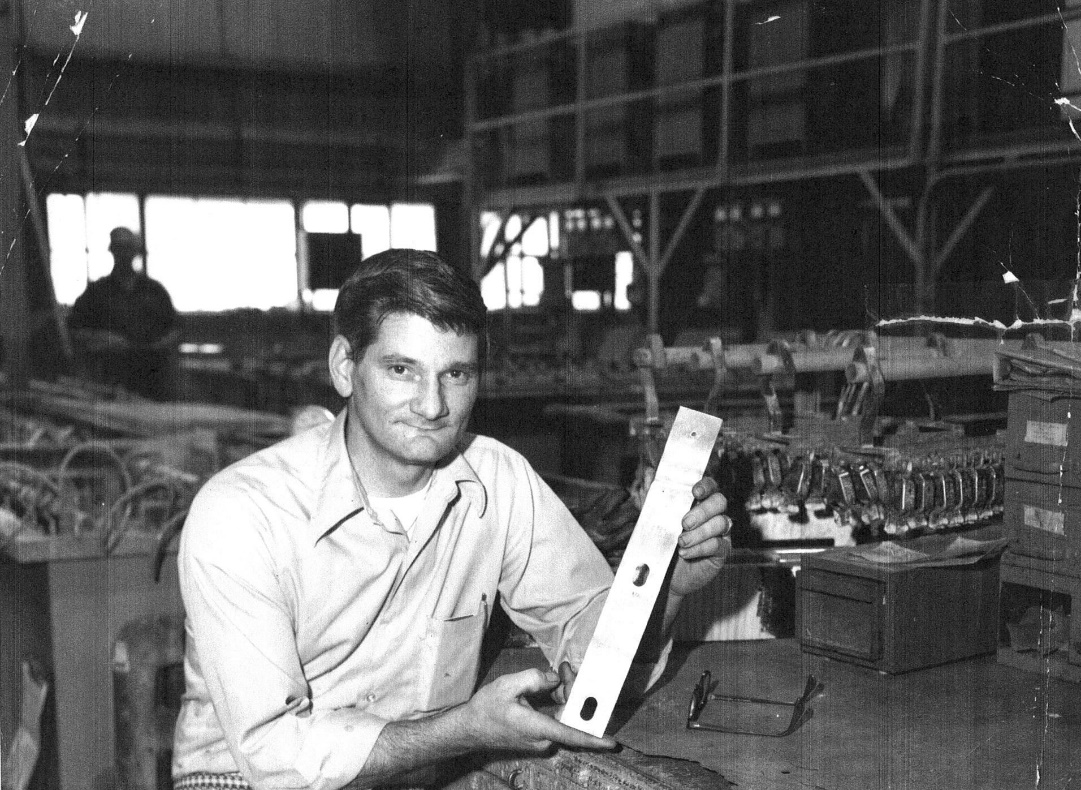

GE worker Gerry Harding.

An invisible disease

Now, says James, so many of her family, friends and colleagues are dying or have passed away.

“It breaks that my heart that at least weekly, somebody else that worked in that plant is going. It’s really frustrating, and I just want these people to be remembered. A lot of them went to work and had no idea that they were at risk. And now the outcome is death or suffering from cancers.”

She says that working with the Alliance has made her feel less alone.

During ODRA meetings, “we would almost be able to complete the sentence of the other people,” says James. “We’ve been in silos but we’re not alone. And everything that we were saying was happening in the other clusters.”

James is now 65, and is starting to feel the effects of having worked in the plant. "It’s an invisible disease; you don’t see it, it’s not like a cut finger or a broken leg," she says. "It was an invisible toxin within our clusters and quite often it rears its ugly head once you’re retired because of the long latency.”

“What happened,” she asks, “why are they not looking at this to help? First off, acknowledge that people have been harmed by this. Secondly, what about our children, our grandchildren? We have to learn so that nobody else has to go through this again, no other generation is put through the tests that they were.”

This is the second part of our new series on occupational exposures. Over the next few weeks, COS will be shining a spotlight on the issue and speaking with occupational disease advocates about the dangers of workplace exposures.

Here is the first part of the series.