Occupational exposures series: Victim's daughter and advocate describes situation as an 'affront to humanity'

Janice Martell‘s father died from Parkinson’s disease after being exposed to aluminum dust in a uranium mine in Ontario. It took the family nine years to get the WISB to acknowledge the link between them, by which time Hobbs had passed away. It was a devastating period for his loved ones.

Stung by the sense of injustice, and a horrendous feeling of isolation for her family, Martell has come together with other Ontario advocates under the Occupational Disease Reform Alliance (ODRA) to try to force change.

She told COS: “We thought that we would try and come together and look at what changes are needed in the system as a whole to be able to carve a path for future workers and to find justice for the ones who are languishing right now in a broken system.”

Exposure in the mines

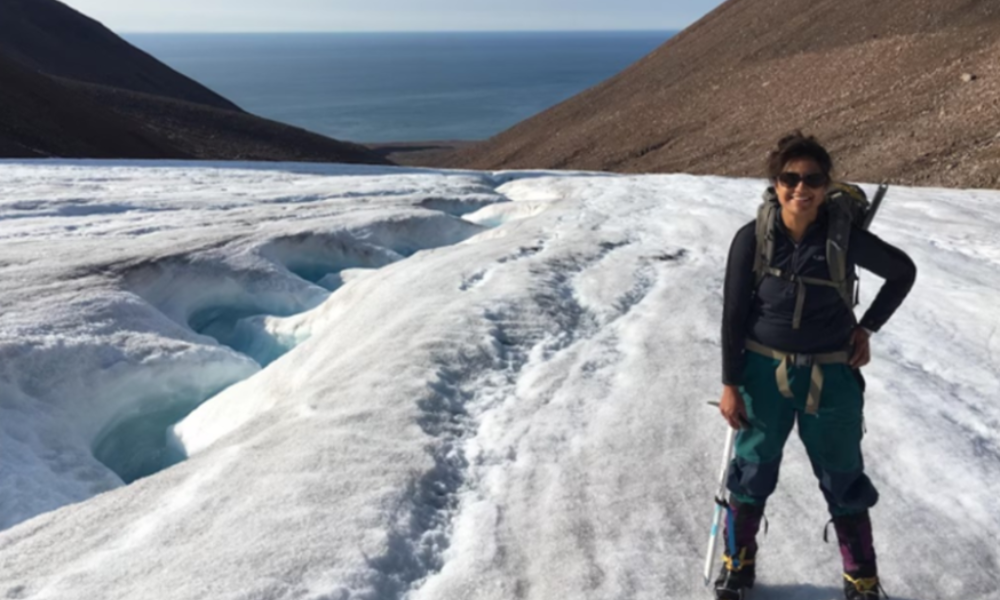

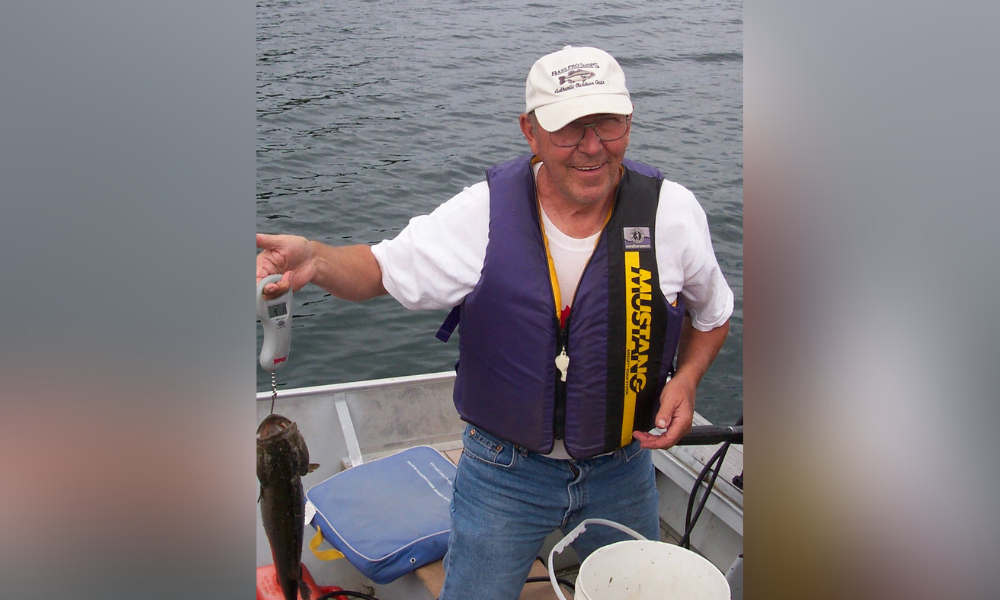

Jim Hobbs, pictured, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2001 after working as an underground miner in Northern Ontario for a number of years, beginning in the nickel and copper mines in Sudbury, Ont., in 1959 when he was only 19 years old.

The first time Hobbs was exposed to McIntyre Powder aluminum dust was in March 1978, when he started at Rio Algom’s Quirke 2 uranium mine in Elliot Lake.

The mine closed in 1990, and Hobbs switched line of work. However, in 2000 he began experiencing the early signs of Parkinson’s and was eventually diagnosed with the disease in 2001.

Hobbs filed a WSIB claim in 2011, which was denied.

Due to the lack of financial support, Hobbs’ family was unable to keep him at home as he reached end-stage Parkinson’s. He died in a nursing home on May 24, 2017.

Shortly after, the WSIB commissioned a study completed in 2020 which found a link between McIntyre Powder and the risk of Parkinson’s.

In October 2020, the WSIB finally granted Hobbs’ claim – three years after his death.

READ MORE: Broadening our definition of occupational diseases

McIntyre Porcupine Mines

Hobbs is far from being an isolated case. An estimated 27,000 miners were exposed to McIntyre Powder aluminum dust.

In the 1920s, the labour landscape was changing and in 1926 silicosis became a compensable industrial disease in Ontario under the Workmen’s Compensation Act.

At the time, the highest silicosis rates were found in the Porcupine mining camps in the Timmins area.

McIntyre Porcupine Mines management decided to investigate ways of addressing the silicosis hazard so as – one can assume – to not be liable for compensation.

“This was an industrial medical treatment controlled by the Northern Ontario mining industry who benefited from exposing their workers to this because it reduced their liability for some silicosis costs,” says Martell.

Martell is also an occupational health coordinator for the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers Inc. (OHCOW) and founded the McIntyre Powder Project, a voluntary registry to document health issues (particularly neurological) in miners or other workers who were exposed to McIntyre Powder aluminum dust in their workplaces.

Debunked theory

An article in the journal New Solutions reveals that in the 1930s, James J. Denny (the mine’s metallurgist) and physician Wilmot D. Robson started conducting experiments on guinea pigs and rabbits which involved inhalation of quartz (pure silica) with and without the addition of aluminum dust.

The article says: “The theory was that, by coating the surface of crystalline silica particles and reducing the surface properties that made them toxic, the aluminum dust would prevent fibrosis of the lung.”

The men published their results in 1939, and the McIntyre Porcupine Mines patented their aluminum therapy shortly after.

Uncontrolled clinical trials began in 1940, funded by Ontario Mining Association mines and with the assistance of the Ontario Workmen’s Compensation Board.

Between 1940 and 1943, clinical trials were conducted on 47 miners.

McIntyre was not the only company conducting these kinds of tests, similar experiments were happening in the U.S.

In any case, the results yielded by these tests were flawed and by more rigorous scientific standards the effectiveness of aluminum dust as a treatment for silicosis was unproven – and has since been debunked.

Nevertheless, from 1943 to 1979, miners in Northern Ontario mining communities were exposed to McIntyre Powder (i.e. aluminium dust). The powder was used as a mandatory medical treatment which involved workers forcibly inhaling the powder.

Miners were locked in a room each work shift where aluminum dust was blown into the room using compressed air.

Union action brought national attention to the condition of uranium miners in Elliot Lake (including exposure to silicosis). In 1979 the Ontario Ministry of Labour commissioned a scientific review and subsequently shut down the use of McIntyre Powder in the mines shortly after.

But the story doesn’t stop there.

READ MORE: The new Radium Girls?

Occupational exposures

Because though the dust had been proven to be ineffective against silicosis, it was far from benign.

And as is the case with many occupational exposures, the effects of the powder were only felt years later.

“Occupational diseases are so hidden, they’re things that happen after people retire or are later in their career. The things that they were exposed to 10, 20 or 30 years ago are the real culprits and so we don’t really see them,” says Martell. “With McIntyre Powder, the whole issue was hidden. I’d never heard about it until 2011 – and I’m a miner’s daughter.”

Martell first heard about the powder while having a casual conversation about work with her father, who revealed that he had been exposed to the powder:

“It’s horrifying to stumble across something like this […] it’s such an affront to humanity, that these workers were locked in a room and forcibly required to inhale a toxic substance. It just blows my mind – even if they didn’t know that aluminium was harmful, they certainly knew that dust in the lungs was harmful.”

Martell’s McIntyre Powder Project was established in April 2015. The project is a place for miners to voluntarily register and document their health issues.

“When you’re dealing with an occupational disease, it is very isolating and it’s a really devastating experience for workers and their families. When you’re trying to fight this on your own, it’s very intimidating [and] it’s hard to focus on anything else other than your loved one who’s struggling,” she says.

There is still more research needed to be done about the link between aluminum dust and occupational illnesses.

Aside from Parkinson’s, research has also revealed a link between McIntyre Powder and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). There are also most likely a host of other illnesses, Martell says that there is currently research into a link between exposure to the aluminum dust and sarcoidosis.

READ MORE: WSIB launching Scientific Advisory Table for Occupational Disease

Demands

The ODRA has four demands:

The main one is that it wants the WSIB to recognize occupational diseases when they are higher than the levels that you see out in the community.

“We have to look at these workers, and get a handle on the scope of occupational disease by keeping track of what workers are exposed to on the job, and monitoring their health over their lifetimes. If we’re not doing that, we’re going to miss the connections.”

Martell says that we can solve this issue by having a national system to monitor what workers are exposed to, document what they’re exposed to and link it with their health records to cross-reference occupations, exposures and diseases.

For example, had they not raised the alarm, Martell says that no link would have been found between McIntyre Powder and Parkinson’s because no research was being done.

One of the big hurdles facing affected workers wishing to apply for compensation is that insurance and compensation boards throughout Canada demand a high level of scientific certainty, with many claims being denied as idiopathic (i.e. of unknown cause), says Martell.

“It’s really important that we challenge this conventional wisdom,” she says.

And so, the two other demands that the group is making are expanding the list of presumptive illnesses, and considering a combined and cumulative exposure effects.

Martell says that the current procedure is that if a worker is exposed to multiple toxic elements, compensation boards will look at the threshold limit value individually for each of those elements. And as long as you’re under the value, she says, then the board considers that the workplace did not cause the illness.

“They need to change their thinking on that and look at the combined effects and the cumulative effects. If you are exposed to something for years, those effects are cumulative. Those things have cumulative impacts.”

The group is also asking for legislation that will implement more oversight and accountability of the WSIB’s powers.

Hurdles

Why are there so many hurdles when it comes to diagnosis and compensation?

One of the problems for those suffering from an occupational disease is that by the time they are diagnosed, it is usually too late. Companies may be gone, union locals have been shut down, and no one is making the connection between exposure and illness. Even those suffering from the illness themselves may not know that have an occupational disease.

Legislative action may not be taken because some of the toxic elements of yesteryear are no longer a threat. Health and safety has made strides in the last few years, but that does not mean that workers previously exposed to toxic workplaces are no longer ill.

Martell also decries a lack of funding around research into occupational exposures.

In addition, other factors may come into play such as gender or class. Workers from lower-income backgrounds or from marginalized communities have historically been taken advantage of, and often find that they are powerless; not able to afford the legal fees to fight claims decisions.

Despite her father’s passing, Martell is determined to get justice – not just for her father but for all the other miners affected:

“He is my reason to start this, and now all of the others are my reason to finish it.”

Says Martell: “Workers are the evidence of occupational disease […] We have that knowledge, and that knowledge is valid. And it needs to be applied in compensating cases, in recognizing occupational diseases. That’s the only way we’re going to turn the corner on this.”

Source:

T.L., Guidotti, J. Martell. Trading One Risk for Another: Consequences of the Unauthenticated Treatment and Prevention of Silicosis in Ontario Miners in the McIntyre Powder Aluminum Inhalation Program. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental Occupational Health Policy, August 2021: <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/10482911211037007>

This is the first part of our new series on occupational exposures. Over the next few weeks, COS will be shining a spotlight on the issue and speaking with occupational disease advocates about the dangers of workplace exposures.