Chemicals hazards are in every workplace – even at home

When it comes to chemical exposure, almost every workplace in Canada is concerned in some way.

From workers in chemical plants to offices where substances like bleach or surface disinfectants may be lying around (especially with increased hygiene protocols around COVID-19), most workers are brought into contact with chemicals in some capacity.

Knowing how to properly handle and read labels is an imperative.

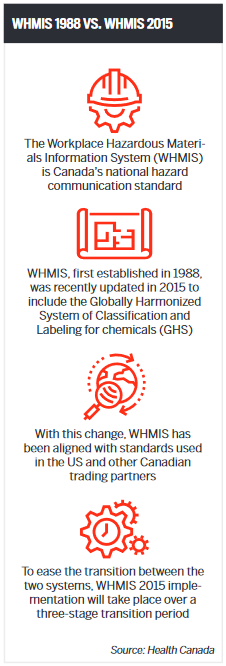

The Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS), first established in 1988, was updated in 2015 and is regulated on a provincial, territorial and federal level in Canada. WHMIS ensures that employers and workers are kept up to date with information about hazardous products they may come into contact with in the workplace.

Safety data sheets (SDSs) for such products are required — they provide information about the products, and advice on safety precautions to take when handling them.

WHMIS Health Hazard classes

WHMIS Health Hazard classes

WHMIS 2015 classifies chemical hazards into 2 groups: physical hazards and health hazards. These groups are further broken down by hazard class with 20 physical hazard classes, that describe harm such as fires or explosions, and twelve health hazard classes, defining the types of harm that can occur to humans.

Each of the health hazards have their own concerns:

“The first category is what they call acute toxicity, which means that it’s immediately harmful to your health — either by swallowing or through skin contact, or by inhaling a single or multiple doses over a short period of time,” says Lisa Hallsworth, CEO, Rillea Technologies.

The next two categories are skin corrosion or irritation, and eye damage or eye irritation. These are products that can burn your skin or damage your eyes, and our data tells us that in a collection of 100 workplace chemicals, over 40 would typically have these hazards.

“The fourth category is respiratory or skin sensitivity. These are chemicals that can cause occupational asthma or an allergic reaction,” says Hallsworth. Such products include weed killers or expandable foams.

The fifth category is germ cell mutagenicity. “These are chemicals that can alter your DNA. The thing about these chemicals is that you can pass the damaged or altered cells along to your children and through generations,” says Hallsworth, and include products like gasoline and spray paints.

The sixth category, carcinogenicity, includes chemical products that are known or suspected to cause cancer.

“The next category is reproductive toxicity. So these are chemicals that are known to harm the reproductive organs in both men and women or can harm an unborn or breastfeeding child,” says Hallsworth. “We see these hazards a lot in solvents and auto maintenance products, and in some graffiti removers.”

The next two categories are specific target organ toxicity — single exposure and repeated exposure.

“These are chemicals that can target an organ of your body; so they can harm, for example, your kidneys or your lungs or your liver. And it can be either a single exposure, or it can happen over multiple exposures,” she says.

Category ten is aspiration (or inhaled) hazard, which targets the lungs. The eleventh category is biohazardous infectious materials, which are very much a concern at the moment due to COVID-19.

The last category is health hazards not otherwise classified. These can either be acute, or the result of repeated exposure.

Millions of chemicals

“Chemicals really do make our jobs easier,” says Hallsworth, but it’s essential to know how to use them in a safe way.

“It’s really important for us to remember that the chemical industry has grown by about five per cent every year for the last few years,” says Hallsworth. “In the last 30 years, we have so many more products on the market that just weren’t there before.”

This is obviously for our convenience, but it also creates more hazards. And it is very hard for governments to truly regulate what is harmful and what can be sold because there are millions of chemical products out there.

And how do you see if someone has been exposed to chemical hazards — of course there are visible injuries such as burns, redness or rashes — but how to measure unseen hazards?

“This is super challenging, there's about 180 million chemical substances registered in the Chemical Abstracts Service,” Hallsworth explains. There are companies that build instruments to test for some of the common specific hazards, such as benzene or silica dust.

That is why WHMIS documents are so important, because when you look at the product that you are going to use, you can see how the supplier classified the potential harm of the product and you can look at the ingredient level for the harmful ingredients, then apply a precautionary approach by either choosing not to use the product or having the correct ventilation, for example, or personal protective equipment (PPE).

Burns and irritation

One of the most common hazards for most workers when it comes to chemical exposure is chemical burn or irritation. A chemical burn occurs when skin or tissues (such as eyes) come into contact with an irritant or corrosive chemical. In some cases, if swallowed, it can cause burns on the tongue, esophagus and stomach tissue.

“Chemical burns occur when skin or eye tissue are exposed to strong acidic or basic chemicals,” says David Wootten, National Prevor Product Manager.

The aggressiveness of acids and bases is determined by the pH scale of the chemical involved, which ranges from 1 to 14, he says. Strong acids can have a pH of one or less, while strong bases can have a pH of 14. Irritant group chemicals such as oxidizers, reducing agents, chelating solutions and solvents present a lesser risk of permanent injury.

Wounds Canada says that every year, thousands of Canadians sustain a burn injury. Some of the most common products that can cause chemical burns include car battery acid, bleach, ammonia, denture cleaner, teeth-whitening products, pool cleaning products, oven cleaner and lye.

“The first and most important step to take after exposure to an aggressive chemical is to provide mechanical removal from the surface of the skin or eye tissue,” says Wootten.

Accessing the closest device such as an emergency shower or eyewash (ESEW) station or personal wash station as outlined in the ANSI Z358.1 standard will help limit exposure time, thus helping to reduce the penetration of the chemical into tissue cells.

Read next: How to find the best eyewash stations for your staff

Case study: Emergency Shower and Eyewash Stations

Taking the example of ESEW stations as a way to manage burns and irritation, there are a number of benefits — but also limitations to using water.

“Water delivered through an ESEW station provides benefits such as mechanical removal, diluting and helping to cool skin or eye tissue, says Wootten.

It is also important to understand that water is a simple passive rinse with limited backend effects. That is why many people who do get exposed to an aggressive chemical and immediately rinse with water, still suffer serious life altering injuries.”

Wootten says that the limitations of water include the following:

- Water can only dilute which means there is no active effect on the aggressive acidic or basic ions resulting in a very slow return to establishing a safe physiological pH on skin or eye tissue.

- Water is naturally hypotonic to the human body which means that water will help diffuse the chemical deeper into tissue cells, potentially exacerbating the injury.

- Accessing ESEW within 10 seconds or 55 feet is not always achievable based on many factors — most important of which are the extent of the victim’s injuries; their ability to get to the ESEW equipment within 10 seconds; whether they have visual impairment, and if so, whether there is a co-worker nearby to assist them; and whether the equipment has been maintained to function properly.

Based on the above, water can be seen as a “passive” rinse, while other, newer products are considered “active” rinses.

“The difference between the two is that while water will provide benefits to anyone who has been exposed to an aggressive agent, it won’t always prevent burns and other complications from happening. Therefore, we need to look at what we need to have happen while mechanical rinsing is occurring,” he says.

An active solution based on the following could improve results, says Wootten, because:

- A hypertonic action prevents the ingress of the chemical and draws it back to the tissue surface.

- A chelating action attracts, fixes to and absorbs the acidic or basic ions, which helps to restore the victim’s skin or eye tissue’s physiological pH rapidly.

- It is amphoteric to opposing chemical reactions, meaning its efficacy is established on acids vs bases, oxidizers vs reducing agents, chelating agents and solvents etc.

So what kind of active solutions exist currently?

“Phosphate and borate buffered solutions are considered active but have limited capacity,” says Wootten. “Borate buffered solutions are designed for basic chemicals but are much less efficient on acidic chemicals, and phosphate buffer solutions designed for acidic chemicals are less efficient on basic chemicals. Most importantly, phosphate buffers can present the risk of corneal calcification.”

The most efficient active solution, he says, combines the mechanical removal effect, the reverse hypertonic draw through tissue cells, the rapid normalization of the tissue pH and is equally effective on chemicals in all classes.

“When it comes to managing chemical exposure injuries in the workplace, having ESEW equipment is important, but just being compliant is not enough. Organizations across Canada and around the globe are ensuring their workers have access the right active decontamination solutions. There is a better method for managing chemical burn injures,” says Wootten.

As more and more chemicals enter the market, it is important to ensure that the equipment and solutions that we use are also updated so as to always ensure optimal worker safety.

Educating workers

Educating workers

As well as having the right equipment, educating workers and employers is paramount to worker safety. Because employees will bring this education home to their families.

Hallsworth mentions that in some jurisdictions like the EU, regulators are looking into not only the hazards of individual products, but how products might interact. Furthermore, they are looking at PPE and equipment that can help to make the user experience safer.

For example, suppliers and manufacturers are looking at potentially including the proper gloves alongside products that can be corrosive to your skin.

“This is a smart approach,” says Hallsworth, “because it tells you immediately that the product is hazardous and that [you] need to wear these gloves to use it safely.”

These initiatives aren’t just valuable for workers and employers, they’re valuable in the private sphere too because at the end of the day, we also use dozens of chemicals in our own homes on a regular basis, from nail polish remover to toilet cleaner.

Case study: Rillea Technologies

Hallsworth’s company, Rillea Technologies, has a product called SDS RiskAssist which allows workers and employers to make informed decisions about the chemical products that they are using.

“I spent 30 years helping to manage people’s chemical exposure in the workplace — and it’s hard. There are a lot of regulations, so reading all the safety data sheets are a great place to start,” says Hallsworth.

But workers and employers also need to do more research on ingredients or hazards that are not identified in the SDS.

Every employer has to have a collection of SDSs. Rillea’s technology reads through all of the SDSs, pulls out the hazard information and organizes it into prioritized groups to more quickly see what the hazards of a product are.

While typical workplaces will have programs on how to correctly use PPE, or fire safety plans, they don’t often have programs to know how to deal with something that’s fatal if inhaled, or that is a carcinogen or reproductive toxicant, says Hallsworth.

Rillea has also released a recent version which allows the user to compare chemicals by their hazard — something that has come in handy for COVID-19 disinfectants as there are so many of them.

“It really allows people to make safer choices for their employees,” says Hallsworth.

“It’s a huge amount of work to understand how chemicals can hurt you and how you, as an employer, are obligated to protect your employees against certain ingredients,” she says.

Rillea’s software enables users to educate themselves in chunks — and in private.

For example, women who are considering or think that they are expecting a child but don’t want to let anybody know, can check hazard information discreetly through the software. In the same vein, employers who know that an employee is pregnant can build hazard groups (in this case, reproductive toxicants), to understand which products a pregnant woman should avoid handling.

“The worker can access that information at any time; it's available on their mobile devices,” says Hallsworth.