Mock trial highlights why 'things are never as simple as they seem'

It’s 10:00 a.m. Wednesday morning and the Orillia Opera House has been turned into a courtroom. A boom crane accident involving a loose jib has left a man a quadriplegic. Now the company is on trial, accused of failing to provide sufficient instruction and supervision of a routine task, stowing the jib, and securing it to the crane at the end of the day.

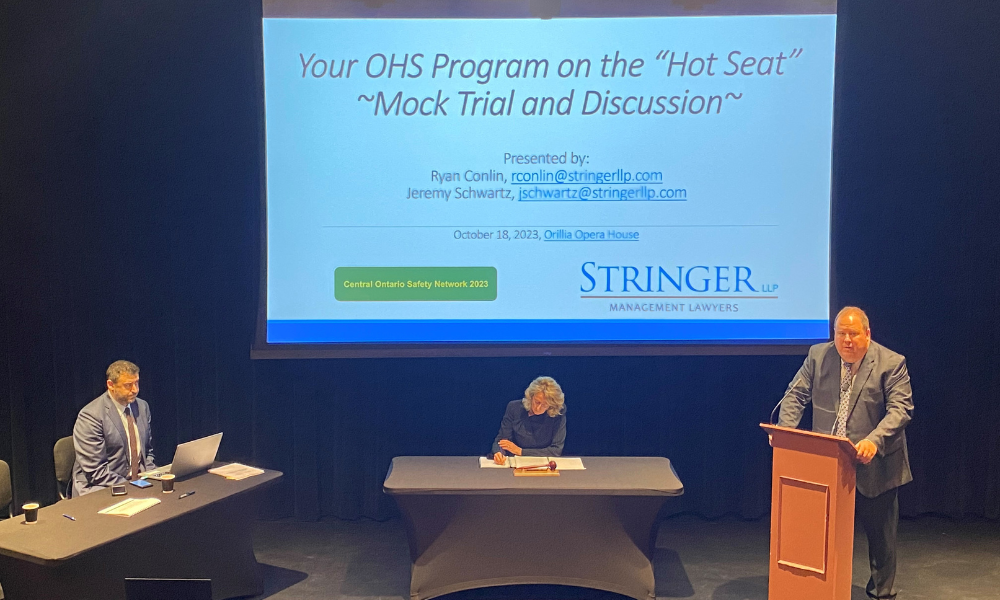

“Our fatality numbers are going up, our lost-time injury numbers are going up, everything's going up,” declares safety consultant Peter Sturm. He is part of the Central Ontario Safety Network, which organized a mock trial titled ‘Your OHS Program On The Hot Seat.’

“I don't think the profession has awareness of what's going to happen if you don't have a good health and safety program in place,” says Sturm, which is why the organization wanted to conduct a mock trial as a learning opportunity for safety leaders in Ontario.

Ryan Conlin and Jeremy Schwartz are partners at Stringer LLP, a firm specializing in employment and labour law. With a little help from attendees, they performed the mock trial while providing context around the legal process and the specific case, which is based on an actual event.

“I'm hoping they take a look at their health and safety program and come to realize how small things can make all the difference in the world,” explains Conlin when asked what he hopes the audience will leave with. “Someone could be a quadriplegic for failing to follow a procedure that everyone thinks is straightforward and simple… things are never as simple as they seem.”

The case hinged on the placement of a hook attached to the jib and its position in relation to one fixed pin on the crane and one removable pin. A critical component to the legal arguments was the manufacturer’s instruction manual. It didn’t clearly outline how to stow the boom jib.

There is both a lesson and a challenge here for health and safety professionals, according to Schwartz. He says, “if you’re going through your policies, procedures, and manuals, can you get the operators, the people who work with this equipment daily, to identify for you with a yellow highlighter what are the most critical, most risky tasks or steps that are either in the manual or not in the manual?”

Schwartz says this process will help identify gaps in a safety system, “and then even if there isn't a legal requirement to have something in writing, that might be an opportunity for improved due diligence. It might be an opportunity to prevent the accident.”

A few dozen safety professionals attended the mock trial, and had opportunities to ask questions throughout, while also benefiting from networking. Janice Campbell is a safety consultant and the owner of Spencer Safety Solutions in Owen Sound, Ontario. This is the closest she’s come to seeing what it’s like when a company’s safety program is put on trial.

“This is a great learning opportunity for someone who's in my position,” says Campbell, “and even for people who are brand new to really understand what is involved when you get into this industry and what you can do to support either your employer, or your clients as a consultant, to prevent them from sitting in those chairs.”

Even though it was theatre, you could feel the heat from the witness chair, and it was obvious to everyone in the room that nobody would want to occupy that seat.

Sturm says as the BCRSP pushes forward with its agenda to establish occupational health and safety as a regulated profession with title protection (like lawyers and engineers) those already working in the field should become more comfortable with the legalities of the job.

“We need to catch up to that, we need to be prepared for it,” suggests Sturm, who also notes that with a regulated profession comes the legal concept of privilege.

“We can get that skill, so that we can work with counsel, but also have that ability to protect the employer,” explains Sturm. “But also get to the get to the heart of the matter and start to look at preventing incidents…all this money is going into the prosecutions, the money's not going back into safety.”

And keeping people safe keeps a safety program off the hot seat.