Occupational exposures series: Advocates say many workers are still missing out on crucial compensation

Two advocates have accused the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) of not taking the health and safety of workers seriously enough. They argue that, as a result, because of prolonged exposure to certain chemicals, we now have intense clusters of occupational diseases.

“Workers gave their lives for these companies, and the WSIB is ignoring [them],” says Rose Wickman, former UNIFOR president at Ventra/Pebra Plastics in Peterborough, Ontario, while advocate and researcher Bob DeMatteo condemned a “lack of regard for taking the health and safety of the workers seriously” in compensation cases that uncovered how these exposures went on for years.”

Wickman and DeMatteo have spent years advocating on behalf of workers in Ontario exposed to toxic substances in their workplace years ago and who are now suffering from a number of what they say are occupational diseases.

Looking back at the number of toxic substances that were in these workplaces, “it’s no wonder that we have the clusters of cancers and other diseases in these workplaces, and probably in many others,” says DeMatteo.

DeMatteo says that, alongside the workers, he and his partners have spent a lot of time trying to bring to light the effects of the exposures: “One of the things we’ve been trying to impress on the Ministry of Labour as well as the WSIB is that as a result of the way things were, as a result of the conditions and the kinds of exposures they had, the kinds of chemicals they handled, we now have these very intense clusters of occupational disease among the workers.”

DeMatteo has notably worked on exposure reports at the former General Electric and Ventra/Pebra Plastics plants in Peterborough, Ontario, and at Neelon Casting in Sudbury, Ont.

The road to recognition – and compensation – can be frustratingly slow. In the case of the more recent Neelon Casting cluster, advocates have been very effectively working with the WSIB on compensation claims. However, those advocating on behalf of other clusters have been less satisfied.

“What about the rest of us?” asks DeMatteo, citing the Pebra/Ventra cluster as an example where claims adjudication has been slow.

“The WSIB has a legal obligation to conduct investigations into occupational diseases, and it’s not doing its job,” says Bob DeMatteo. “Where is the concern for human health? They’ve been so lax in not recognizing the health effects of things like metalworking fluids and a whole series of toxic exposures, and have not altered or lowered the Occupational Exposure Limits (OELs) to reflect the science, and need to invoke the precautionary principle in the face of scientific uncertainty, and to ensure more stringent enforcement of exposure standards.”

With regard to the GE workers, claims have been rejected consistently until recently, he says. The WSIB finally recognized esophageal cancer in two separate cases. Both workers were machinists, and there is strong evidence of a connection between esophageal cancer and cutting fluids.

This connection, however, was ignored at lower-level adjudication in favour of the workers’ exposure to asbestos at the appeal level.

Bob DeMatteo also says that while the WSIB has been good at adjudicating claims relating to asbestos exposures, the response has been less great on other exposures, and with regard to claims “there is so much in the way of inconsistencies going on that it’s troublesome. We’ve seen this in cases where one worker has his or her claim accepted, while another is rejected for the same disease and same exposures, in the same shop.”

“The Board’s adjudication process has not been consistent. It’s not moving forward,” he says. “I think the WSIB has a long way to go to reform.”

The WSIB has recently shed light on its occupational disease strategy, which it says will allow them to achieve a “more responsible and sustainable approach to occupational disease policy and decision-making.” The organization has launched an Occupational Disease Policy Framework Consultation and is looking for feedback from interested stakeholders. Submissions are open until January 31, 2022.

COS has reached out to the WSIB for comment.

Read more: Deadly exposure: new health concerns afflicting 9/11 heroes

Disillusioned

Though he had extensive experience of the workplace, Bob DeMatteo says that he was “quickly disillusioned” when he started to work in the field of occupational health.

His main gripe? “There’s a sense in which there is more interest in protecting the companies on a financial level than making sure that these workplaces are safe and healthy.”

Bob DeMatteo spent 30 years as Director of Health and Safety for the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU).

He became involved with occupational cluster exposures when he was invited to assist in a study on occupational breast cancers led by Drs. James Brophy and Margaret Keith of Windsor University.

“I worked alongside the research team in developing a system for evaluating the exposures in the plastics industry.”

He was later contacted by Jim Gill, former national Director of Health and Safety for the Canadian Auto Workers union (CAW), which has since become UNIFOR.

Gill, based in Peterborough, invited DeMatteo to speak with local workers at the General Electric and Pebra/Ventra Plastics plants.

“Both groups found that their workers’ compensation claims were so stalled and going nowhere. They were having real difficulties with the Workers’ Compensation Board (WCB),” says Bob DeMatteo. “They wanted to know how we could help them with their existing compensation claims.”

(The WCB is the former name of the WSIB.)

Eventually Bob DeMatteo began working with the union and some of the workers to start gathering information. He recruited Dale DeMatteo, a public health researcher, to develop a method of gathering information from workers and reviewing documentation.

Read more: Ontario miners exposed to aluminum dust still fighting for justice

The DeMatteos proposed a retroactive exposure profile study similar to what was used in the breast cancer study to members of the group.

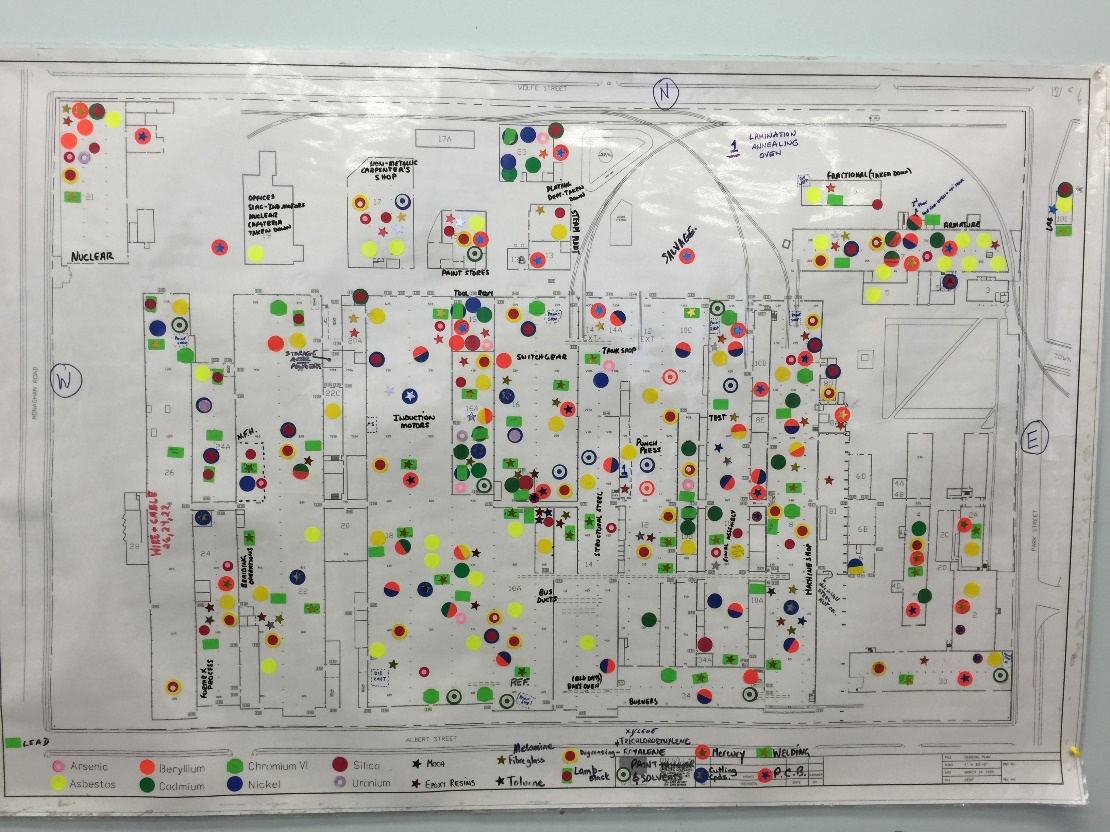

“We [used] what we call a risk-based approach. In other words, what we tried to determine was the risk of being exposed to these various chemicals in the workplace, based on industrial hygiene concepts,” says Bob DeMatteo.

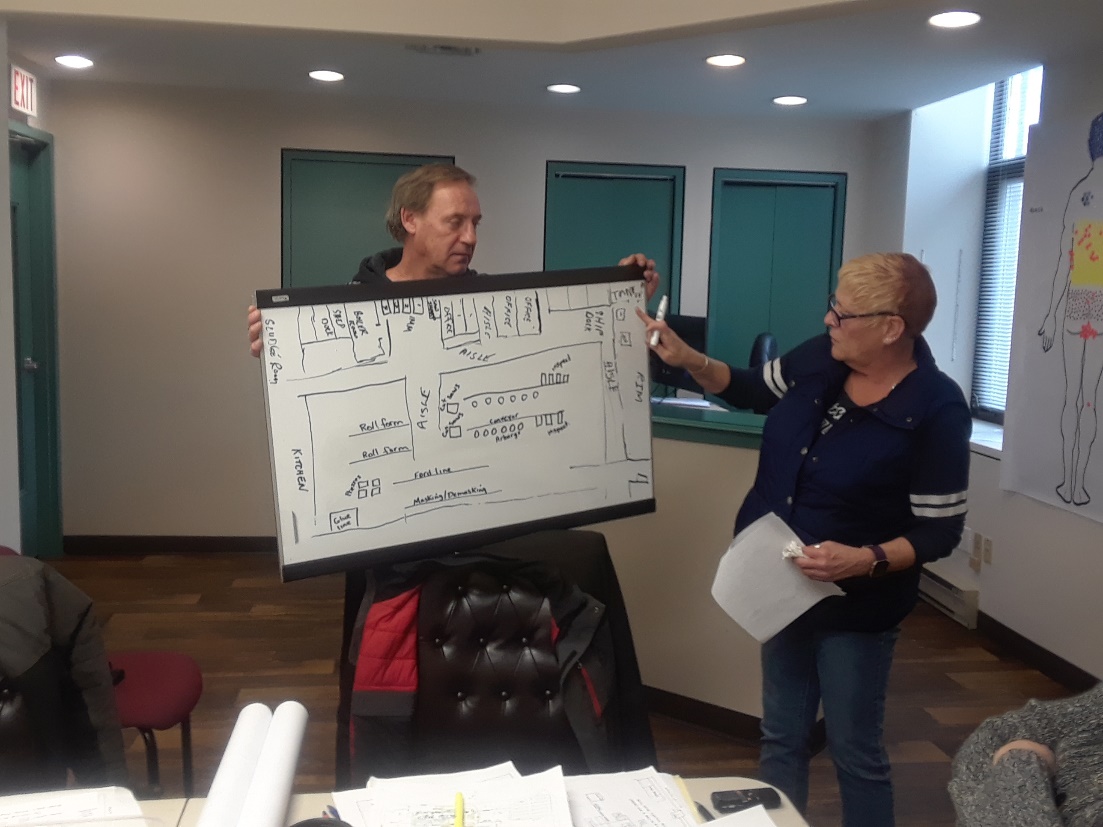

“Before we could even begin to do the work, [the workers] had to educate us on everything about the plant so that we could understand and have a picture of it. In return we educated them in terms of risk assessment,” says Dale DeMatteo. “In order to write the reports we’ve written, we’ve had to put ourselves in workers’ shoes to really understand in detail what they did and how they did it, and the realities of their daily encounters with the workplace.”

The first report they produced was on the GE plant:

“It was quite a burdensome project in a way because we had to take it department by department (there were 24 departments), and break down what chemicals were used there, their physical states, how much of it was used, how they employed it,” says Bob De Matteo.

“From that, we were able to get a profile of what the exposures were like. For example, workers with no gloves or masks hand sanding lead Babbitt bearings up to their elbows in toluene. We also asked questions about symptoms and health effects.”

Brutal conditions

The team used the same method for the Pebra/Ventra Plant, and most recently for the Neelon Casting cluster.

“In each case we uncovered what I would call brutal exposures and work conditions,” says Bob De Matteo.

“In terms of the three reports that we’ve done,” says Dale DeMatteo, “there were some really major similarities. The first one was that the workers in all the plants struggled for their right to the Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) – information on the chemicals they used, and the proper training and equipment.”

“The other thing was that in every one of the plants, there were issues around ventilation that were major, and continued to be a major cause of much of the exposures.”

She also says that there was a problem with access to proper PPE:

“For example, in the [Neelon Casting] foundry they had a small number of aluminized suits that workers would wear when they were working close to the melts. And they would have to share them, so it would be filled with the previous user’s perspiration.”

Dale DeMatteo additionally says that they also found that during inspections, officials were reluctant to write orders: “They were reluctant to take the word of the workers who were experiencing certain problems, whether feeling faint or [having] difficulty breathing.” This was the case for all three plants.

The evidence was based not only on the workers’ description but also on hard evidence provided in reports from the Ministry of Labour, says Bob DeMatteo:

“We don’t take what workers who are in the focus groups tell us for granted, we always cross check and look at hard information to get as much validation and confirmation as possible about what conditions are in the plant. One of the things we do is we look at internal memos, inspection and other reports, etc.”

The researchers indicated that this was a way of triangulating the various sources of information to maintain validation and reliability.

Read more: Why tracking risk of disease in the workplace is a national issue

Lack of recognition

“The lack of recognition of these diseases was an important finding of a Report submitted by Dr. Paul Demers, Director of the Occupational Cancer Research Centre. Occupational disease is really under-recognized by the workers’ compensation system, the Ministry of Labour and Public Health [Cnada],” says Bob DeMatteo/

He explains that through their research, the group discovered that many of the Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) are not health-based limits: “They are simply meeting what is practically achievable rather than making them more stringent and more enforceable so that it has a positive impact on workers’ health. So the protection of workers is unfortunately minimized as a result of this failure.”

Dale DeMatteo adds that another important element they discovered “in all cases” was the quality of the MSDSs:

“So much information was left out because it was deemed to be proprietary. The other thing is that the MSDSs are often incomplete and inconsistent and determined by the manufacturer or the distributor, the later are generally much less complete than the manufacturers.

Government – or some regulatory body – ought to check these so that workers are getting accurate, complete information because the whole system is based on the fact that workers need to be informed, trained, and protected.”

In addition, Bob DeMatteo says that regulators don’t pay enough attention to endocrine disrupting chemicals and that more research needs to be done – and current research needs to be recognized and taken more seriously.

He also decries a lack of funding in support of workers needs:

“We’re working on a shoestring budget,” to do all of the cluster investigations that they have been doing.

So where can workplaces start when it comes to prevention?

Says Dale DeMatteo:

“Before any workers go into a workplace, they should ensure that the ventilation system is adequate for the type of work that’s being done. [And] you need to have proper information in place for workers and make sure that they have access to it, understand it, and are well trained.”

“Equally important, the WSIB and the Ministry of Labour must enhance the recognition of occupational disease for both claims adjudication as well as regulatory development and enforcement,” says Bob DeMatteo.

He also notes that the current under-recognition of disease distorts the regulatory process and prevention efforts.

Says Bob DeMatteo:

“This all requires appropriate funding of the compensation and prevention systems which is not well served by the current plans to divert $3 billion in surplus funds back to the employers’ coffers. These funds are urgently needed to support enhanced recognition of disease claims and the health needs of workers who have been made sick by work”.

This is the sixth part of our new series on occupational exposures. Over the next few weeks, COS will be shining a spotlight on the issue and speaking with occupational disease advocates about the dangers of workplace exposures.

Here are the first (miners exposed to aluminium dust), second (exposures at GE plant in Peterborough), third (exposures at Neelon Casting), fourth (Pebra/Ventra Plastics exposures) and fifth (interview with Dr. Paul Demers) parts of the series.