The provincial government has finally recognized the disease as an occupational illness linked to McIntyre Powder

The Ontario government has formally recognized Parkinson’s as an occupational disease linked to McIntyre Powder.

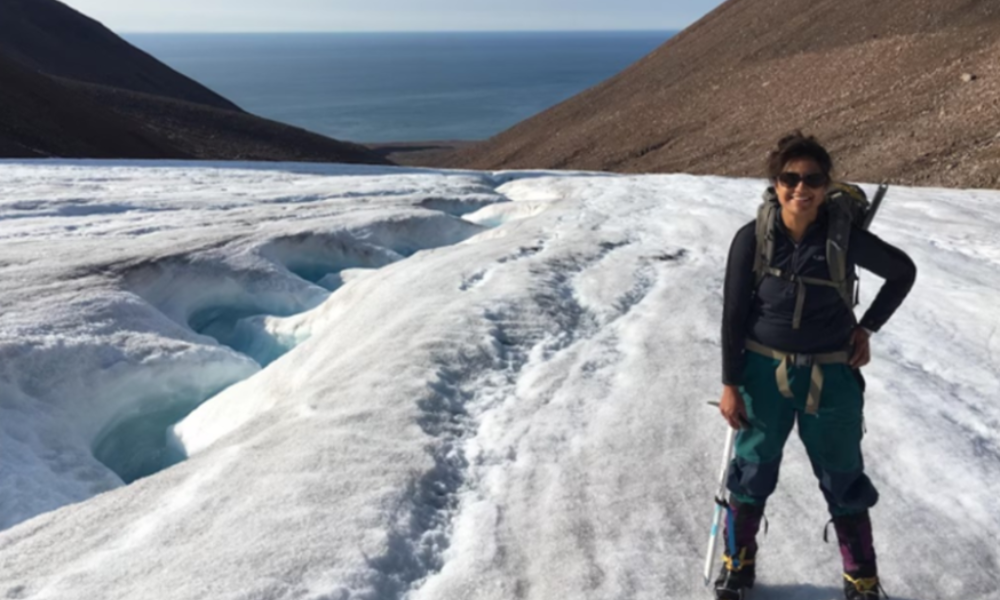

COS spoke with advocate Janice Martell, whose father, Jim, died from Parkinson’s disease after being exposed to aluminium dust in a uranium mine in Ontario.

Between 1943 and 1979, miners in Northern Ontario hard rock mines were exposed to “McIntyre Powder”, a finely ground aluminium powder which was at the time though to prevent silicosis.

Jim’s WSIB compensation claim was denied in 2011 on the basis that there was officially no proven link between exposure to aluminium dust and Parkinson’s.

Later, the WSIB commissioned a study, completed in 2020 by Dr. Paul Demers, which found a statistically significant increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in miners exposed to the powder.

The provincial government has finally made amendments to a regulation under the Workplace Safety and Insurance Act to now formally recognize Parkinson’s as an occupational disease linked to McIntyre powder exposure.

And much of this is thanks to Martell and the tireless work of advocates in Ontario:

“I never set out to convince the WSIB to do the right thing, I set out to compel them. I don’t need them to change their mind on things, I needed to have enough evidence out there that they would be compelled to act,” says Martell.

This change removes the onus on workers to establish a link between the disease and the workplace during claims adjudication with the WSIB. This will enable adjudicators to make decisions more quickly and effectively for affected workers and their families.

In a press release, the Ministry of Labour says that “this will in effect guarantee compensation for workers who have been exposed to McIntyre Powder and developed Parkinson’s Disease.”

“This entrenches it into law, into the regulations. It’s an automatic presumption. It just takes a lot of the burden off of the workers and their families. It’s huge,” says Martell.

Martell has spent years advocating on behalf of her father, and other Ontario miners affected by exposure to the dust.

She and her family are proud of Jim’s legacy – “In life, he was a trailblazer,” says Martell.

Martell says that now her hope is that there be more recognition for other workplace exposures:

“You want everyone to float, you want everyone to be recognized,” she says. “I’m elated for the miners, but I also feel sick for the ones that are still waiting. That weighs on me.”

“The whole system needs to change,” she says, to identify these exposures and stop a constant cycle of diseases. “My ultimate goal is to change the workers’ compensation system, and I have a much clearer vision of what that entails. And it’s a big, bold mission.”

Martell now more broadly wants to work towards system change, she knows it may take potentially years – “I’m not afraid of hard work. I have zero tolerance for lip service. We need to build something that is going to survive political change. We need to build something that embraces the notion that these workers’ lives have meaning and we need to keep them safe.”