Toxicology expert tells COS that Ground Zero horror exposed first-responders to substances now linked to neurological, cardiovascular issues

Many first responders made the ultimate sacrifice on 9/11, but for those who made it out alive, the past 20 years have been far from easy.

Workers present at Ground Zero on 9/11 and the ensuing days were exposed to substances that were later revealed to have adverse effects on the workers’ health.

Now regarded as occupational diseases, first responders developed respiratory issues such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or pulmonary fibrosis, as well as other 9/11-related chronic health conditions. Later, some workers started developing cancers.

But it doesn’t stop there; recently researchers have been looking into potential secondary diseases.

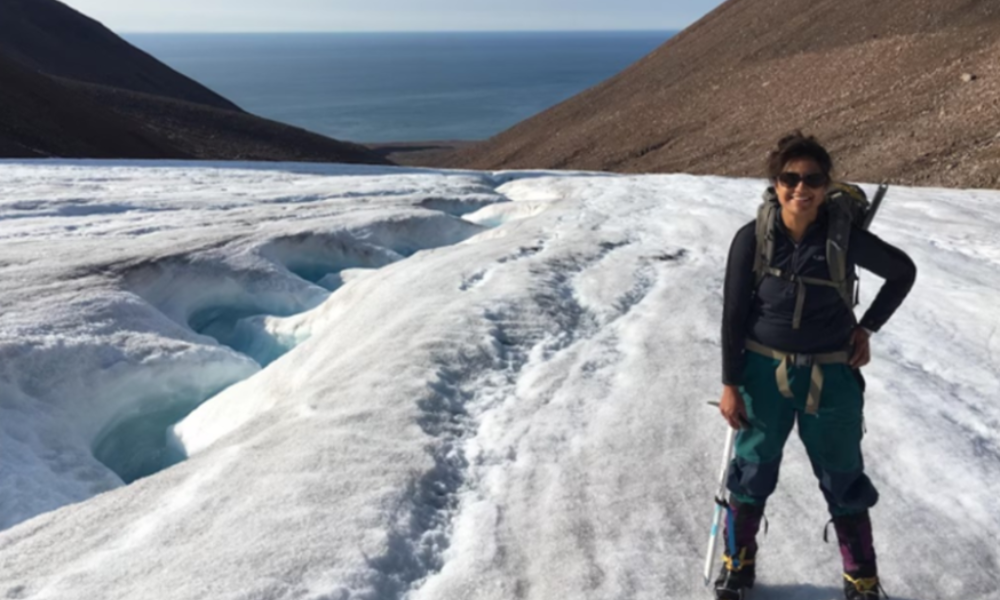

“Not only do people suffer from the obvious respiratory diseases, but there are also implications of secondary diseases that can result from inhalation exposure to the dust,” says Michelle Hernandez, now associate director of occupational toxicology, Merck & Co.

These include health issues affecting other physiological systems including the cardiovascular system, as well as the central nervous system.

Hernandez has recently submitted a paper on the first documented outcomes of World Trade Center dust on neurological tissues.

“There are a lot of unanswered bits of information out there, and the manuscript I recently submitted addresses some initial central nervous system findings, specifically around exposure to the dust and increased anxiety behaviors.”

World Trade Center dust

Hernandez had been researching the topic for years. Her PhD research was centered around the topic of exposure assessment.

“Essentially anything you can be exposed to,” she says, “heavily concentrated on what is called particulate matter – better known as air pollution.”

She had initially started out on another topic but an opportunity presented itself to work on the World Trade Center dust and to pick up where others had left off.

“That was a special opportunity because it’s a topic I had already been involved with before I had even started my PhD project at NYU,” says Hernandez.

Indeed, her Master’s project at Montclair State University was looking at World Trade Center dust effects in cells in vitro, and how they affect certain cell types.

The crux of Hernandez’ research was finding how to correlate health issues developed by those present at the scene on 9/11 and the dust.

“You have all kinds of environmental considerations taking place including diet, exercise, smoking, air pollution – how do you delineate?” She asks.

Around 2010 to 2015, there wasn’t much health data other than in occupational cohorts (such as firefighters, policemen, EMTs, etc.), says Hernandez.

Nevertheless “there was some data that helped us understand that something was going on from these exposures,” she says.

There were notably spirometric abnormalities – doctors use spirometry tests to diagnose conditions such as asthma, COPD, etc.

And the abnormalities tracked included breathing issues, increased incidence of asthma, increased incidence of nasal inflammation, mainly upper and lower respiratory-related issues.

And it is not just first responders who were exposed, local workers and residents, and cleanup crews, were chronically exposed.

Read more: 9/11 20 years on: First responders still fighting for benefits

Particle overloading

One of the biggest issues, says Hernandez, is that the World Trade Center dust wasn’t a single entity exposure scenario, it was full of so many different compounds – both organic and inorganic things.

“It’s really hard from an exposure assessment lens to try and pinpoint what caused these health outcomes. What specific parts of this dust?”, says Hernandez.

The first part of her research was trying to understand how these large particles – which are supposed to technically be unable to be breathed into the lower part of the lungs – could be breathed in, and if so what happens once they are breathed in.

Anything 10 micrometers or smaller is believed to be respirable, but the WTC dust was around 53 micrometers and above.

“I was able to show that due to the large plume that developed, essentially the plume forced its way into people’s airways,” she says, describing it as particle overloading. “You were able to get these particles into the lungs, the deep lung and those particles then elicited inflammation.”

In addition, Hernandez was also able to show what parts of the dust were responsible.

Because the dust was comprised of so many different substances.

There were a lot of different metals, she says, and there was a lot of silica, concrete, gypsum and synthetic vitreous fibers.

And the cumulative effect of these substances together could exacerbate negative outcomes.

The dust, thought initially to have been ‘harmless’, proved to be anything but.

A disease of time

With regards to the illnesses stemming from the exposure, some developed faster than others.

Hernandez (who studied rodent models and cell culture models for her research) found that respiratory issues developed relatively quickly after exposure.

Some of the inflammation subsided over time, some didn’t.

The exposure scenario is so varied among the people who were exposed, says Hernandez:

“Did [the workers] have PPE? What was their ventilation rate? How long were they there? How close were they to the burning pile?”

There are so many different scenarios to try and account for, but she says that from an acute exposure standpoint inflammation immediately happened in the airways.

“With regards to first responders, published studies have shown an increased incidence of upper respiratory-associated diseases, digestive conditions and mental health conditions including PTSD” says Hernandez.

When she started her research, there weren’t many, if any specific cancers associated with exposure to the dust at the time. However, Hernandez says that near the end of her PhD, prostate cancer was correlated.

Since, there have been a number of other cancers added to the World Trade Center Health Registry.

Like many occupational diseases, there is a latency period for these cancers.

“Diseases take time to develop,” she says, “and cancer is a disease of time.”

Ultimately, providing the link between the dust and the illnesses first responders have since developed is of the utmost importance. It is the scientific proof needed for recognition and compensation.

And with more potential diseases being discovered, we need to continue to invest in research to give the 9/11 heroes their due.