Nothing was the same after a decade which saw the acceleration of workers’ rights

Welcome back to our ‘OHS through the years’ series. In this series, COS is looking back at the history of workplace health and safety in Canada. Our first entry covered the beginnings of the safety movement in the 1880s. Our second installment covered advances made from the 1910s through to the 1960s.

Today we’ll be taking a look at the 1970s, truly the decade where workplace health and safety exploded. A lot of the fundamentals we see today stem from important conversations and legislation that were explored and put into place during that decade.

One important figure of that decade in Ontario, and throughout the rest of Canada, was James Milton Ham. Considered the “father of occupational health and safety in Canada”, he was instrumental in the development of safe workplaces in the province and in the country as a whole.

The father of occupational health and safety

Ham (1920 – 1997) served as the 10th president of the University of Toronto (1978 – 1983). He had initially gone to the University as a student of Electrical Engineering in 1939 and graduated in 1943 with the highest marks ever awarded to a student in the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering. Ham had an illustrious academic career, graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1952 with a Science Doctorate, and eventually becoming president of the University of Toronto.

More relevantly to OHS, Ham was appointed Chairman to the Royal Commission on Health and Safety of Workers in Mines (known more commonly as the “Ham Commission”) in 1974. The report that this commission yielded changed occupational health and safety forever, yet changes were taking place not only in Ontario but other provinces too.

Read more: Workplace safety in Canada: Where it all started

Saskatchewan’s landmark act

In 1972, Saskatchewan passed the Occupational Health Act – the first of its kind in Canada.

In North America, the United States had previously enacted the Occupational Safety and Health Act in 1970 (which became effective in April 1971). With previous OHS legislation in Canada being influenced by the UK and Germany, we could posit that the US act had some effect on Canada.

In their book, On the Side of the People: A History of Labour in Saskatchewan, Jim Warren and Kathleen Carlisle say that at the time Saskatchewan as a province was the national leader in the number of workers per capita killed or injured on the job (Coteau Books, 2005):

“What the labour movement was looking for was a plan based on the principle of prevention…At the time, sections of the business community argued that workers were inherently careless and this was the primary cause of workplace illness and injury…Saskatchewan’s Department of Labour rejected this idea, assuming instead that accidents were related to inherently hazardous workplaces.”

This act instituted the concept of internal responsibility system by making health and safety a joint responsibility of both the employer and employees, and requiring the establishment of a fundamental aspect of occupational health and safety: joint health and safety committees.

The Occupational Health Act spelled out the three essential rights of workers:

- The right to know about hazards and dangers in the workplace;

- The right to participate in health and safety issues through a workplace committee;

- The right to refuse unsafe work.

With the passing of this landmark act, Saskatchewan paved the way for safer workplaces and cemented its place in occupational health and safety history.

Warren and Carlisle highlight Walter Smishek, Gordon Snyder, Ross Hale and Bill Gilbey as important actors in Saskatchewan’s fight for a safer workplace, as well as Bob Sass. Sass was promoted in 1974 to Saskatchewan’s Associate Deputy Minister of Labour, and was also instrumental in the development of WHMIS – which we shall cover in our next entry in this series.

Read more: OHS in Canada: Ontario leads the way

Explosive strike in Elliot Lake

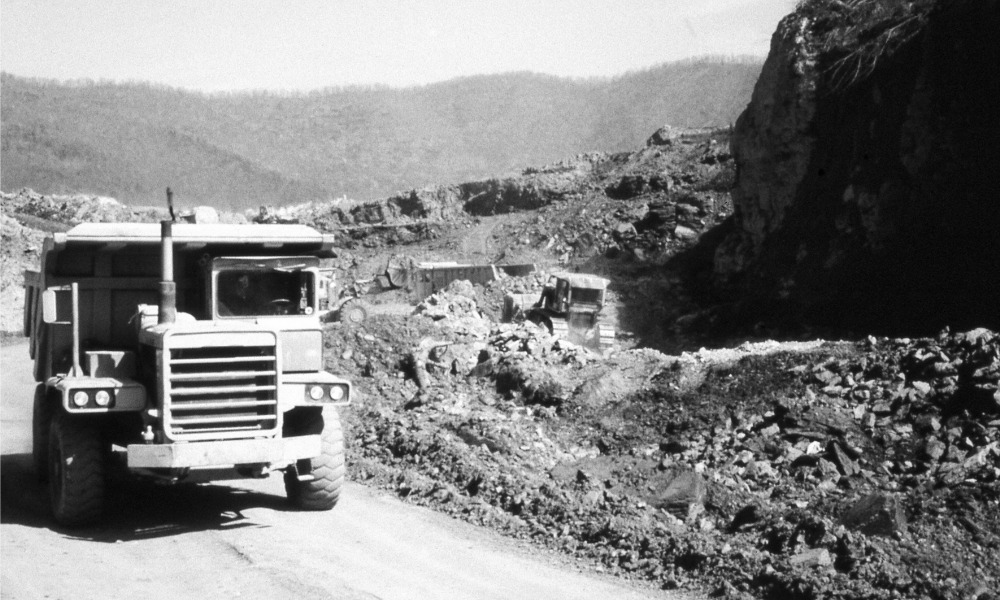

With these important changes being made in Saskatchewan, strides were also being made in Ontario – and it all really boils down to the Elliot Lake strike in 1974.

On April 18, 1974, around 1,000 miners from the Denison uranium mine in Elliot Lake, ON, went on a three-week wildcat strike. The reason? Unsafe work conditions. Indeed, members of the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) found out that the cause behind the high rate of lung cancer among mining workers was due to radiation. Furthermore, this was something that the Ontario government had apparently been aware of but had not informed the miners.

“The news hit the workers like a bombshell. They did not even know the government was studying them…The workers were particularly angry that both the employer and the government had long known the workers were being exposed to dangerous radon gas but had said and done nothing,” write Jason Foster and Bob Barnetson (Health and Safety in Canadian Workplaces, AU Press, 2016).

Read more: Evolution of health and safety in the last 50 years

Ham Report

Then-premier William Davis decided to launch a royal commission to investigate health and safety in mines in Ontario and thus the Ham Commission was born in 1974.

“[Ham] was appointed to specifically look into that situation, but then look more broadly [at worker safety]. His report was considered to be very fair minded,” says Laurel MacDowell, a professor of history at the University of Toronto.

The Commission reported its findings in 1975 (the “Ham Report”) and made over 100 recommendations, including the creation of joint committees. In 1976, one of the results of the Ham Report was the establishment of the Occupational Health and Safety Division in the Ministry of Health, which included mines safety, construction safety, industrial safety and occupational health.

“[Government] began to get the concept that there should be procedures whereby employees shouldn't be forced to work if there's a problem,” says MacDowell, “It was a process of education and pressure from the labor movement.”

She says that the report resulted from talking to workers and employers and finding that “employers really did have responsibility for the health and safety of their employees – and that there should be a framework, not just in mining workplaces, but in all workplaces.”

Also in 1976, Bill 139 established the Employee’s Health and Safety Act, and the Board of Canadian Registered Safety Professionals (BCRSP) was formed as a certification body for safety professionals.

Read more: 7 most common occupational diseases

Ontario’s Occupational Health and Safety Act

All of these efforts culminated in Ontario in 1978 with Bill 70, which finally established the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA). The Canadian Centre of Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS) was established that same year. OHSA, which covered most workplaces, combined previous OHS legislation, including the Construction Safety Act, the Mining Act (Part IX), the Employees Health and Safety Act and the Industrial Safety Act.

“Having some kind of legislative framework really made a huge difference because it put the onus on all of the parties, not just the workers. It was the government and employer responsibility as well,” MacDowell says.

So as we can see, changes which arose in the 1970s truly revolutionised occupational health and safety. Ontario and Saskatchewan were trailblazers in the fight for a safer workplace. Furthermore, we owe it all to the labour movement, unions and forward-thinking individuals who fought to establish a safe environment for all workers.

Sources:

https://discoverarchives.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ham-james-m-oral-history

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/highlights-in-canadian-labour-history-1.850282

https://www.labour.gov.on.ca/english/hs/faqs/molrole.php

https://wohis.org/history/

https://magazine.cim.org/en/voices/the-strike-that-saved-lives/

https://www.thesafetymag.com/ca/topics/safety-and-ppe/evolution-of-health-and-safety-in-the-last-50-years/183251

https://esask.uregina.ca/entry/sass_robert_1937-.jsp