Researcher's death exposes lack of oversight, training, and national protocols

The death of internationally renowned Arctic researcher Maya Bhatia during fieldwork on the Jakeman Glacier near Grise Fiord, Nunavut, raises significant questions about how scientific expeditions in Canada’s North are planned and regulated. Unlike other international bodies that operate in polar environments, Arctic fieldwork in Canada remains largely self-regulated, with no federal agency overseeing risk management or enforcing safety practices.

Researchers, safety experts, and field professionals say that needs to change.

International standards: A model Canada doesn’t follow

Institutions such as the British Antarctic Survey, NASA, and the Danish Geological Survey enforce stringent safety protocols, including mandatory glacier training, defined guide-to-researcher ratios, and pre-departure safety clearances. In Canada’s Arctic, no such standards exist.

Bhatia’s widower, Benjamin Gready, believes the presence of a guide, trained in safely traversing glaciers and polar environments, could have prevented his wife’s death.

Dave Stark, director of risk management at Yamnuska Mountain Adventures, has nearly 40 years of experience as a mountain and wilderness guide. In 2024, during the research season following Bhatia’s death, the University of Alberta hired Stark to travel to Grise Fiord for three weeks to assess safety and report back to the institution.

“In the Antarctic, you don’t go out unless you’ve met a defined set of safety criteria,” Stark says. “In Canada, that kind of gatekeeping doesn’t really exist.”

He says the lack of centralized protocols forces individual researchers and institutions to assess risks and set their own standards.

“There are well-developed protocols elsewhere that simply don’t exist here,” he says. “What’s missing is an institutionalized culture of pre-field readiness, backed by formal training and enforced expectations.”

Safety by funding and initiative

In Canada, researchers develop their own field health and safety plans, which their institutions must approve. But the level of preparedness varies widely, depending on available resources, institutional support, and experience.

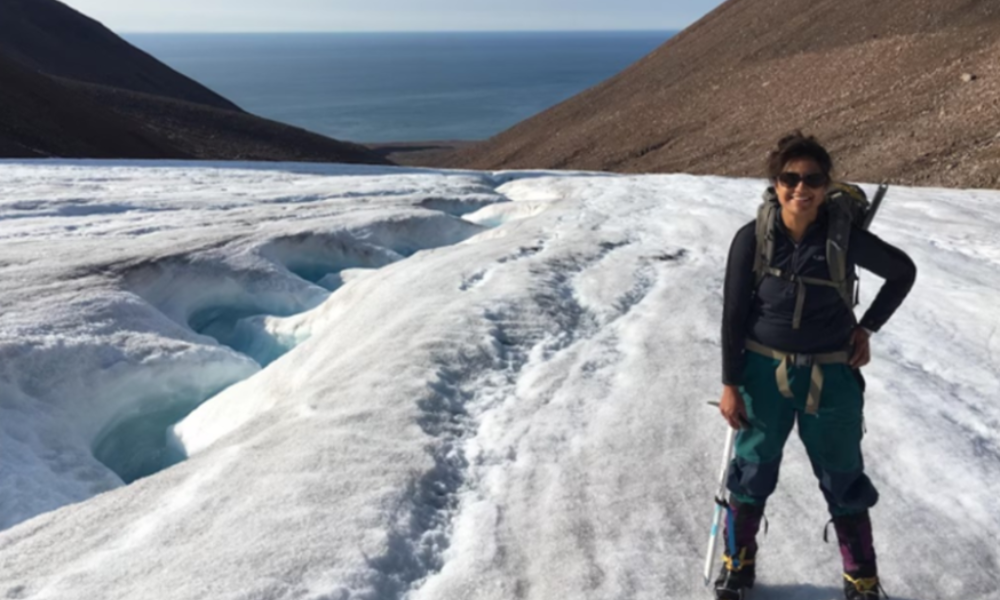

(Grise Fiord, Nunavut on August 15, 2023, one day before Maya Bhatia went missing on the Jakeman Glacier. Source: David Didier’s witness statement)

(Grise Fiord, Nunavut on August 15, 2023, one day before Maya Bhatia went missing on the Jakeman Glacier. Source: David Didier’s witness statement)

David Didier leads an Arctic research team from the University of Quebec at Rimouski and was at the Jakeman Glacier when Bhatia died. He says much of the burden falls directly on individual teams.

“We're not professional safety experts,” Didier says. “We do what we can, but that’s not the same as having someone trained to assess evolving risks in real time.”

Since the incident, Didier heavily invests in training students and his team. He spends approximately $15,000 on glacier rescue equipment and training in glacier walking, boating, and remote emergency response.

“We’ve done this ourselves because we can—because we’ve secured enough funding. But that’s not a sustainable model, and it’s not accessible to every research group,” he says.

During the 2023 research season, Bhatia, Didier, and a lead researcher from the University of Manitoba were jointly responsible for safety operations. While experienced in polar environments, none were experts in glacier rescue or held any formal oversight roles. When the team deviates from the original plan, no formal system exists to reassess or intervene.

“She was capable and experienced, but she didn’t have a second set of eyes on the ground focused solely on safety,” Didier says. “We were just scientists trying to do our jobs.”

Experts say fragmentation is the problem

Dylan Short, managing director of The Redlands Group and a specialist in workplace safety investigations, says the lack of coordination across institutions, funders, and agencies leaves Arctic researchers vulnerable.

“There’s no consistency across institutions,” Short says. “And without a central framework, it’s hard to even say what minimum safety standards should look like—let alone enforce them.”

Short acknowledges that Canada’s internal responsibility system places safety accountability on everyone involved—from researchers to institutions—but says the model breaks down in complex, remote operations.

“When you’ve got multiple universities, federal agencies, local communities, and private contractors all involved in a single expedition, clarity of responsibility gets lost,” he says.

PCSP response offers limited clarity on safety role

Canadian Occupational Safety reached out to the Polar Continental Shelf Program (PCSP), the federal agency that provides funding and logistical support for Arctic researchers.

In its response, it avoids all questions specifically related to the Bhatia incident. The agency also declines to comment on whether it has changed its processes or position since the fatality.

Instead, PCSP reiterates it provides “safe and reliable logistics support” to Arctic researchers but does not explain what constitutes “safe” logistics beyond transportation and equipment delivery.

“Field health and safety is the responsibility of Principal Investigators and their research institutions, including putting in place appropriate field health and safety plans,” the agency states.

PCSP adds that it requires researchers to submit a safety plan approved by their institution’s Occupational Health and Safety authority and ensure that team members hold valid First Aid certification. Researchers must also review the PCSP Arctic Operations Manual and program terms and conditions.

While the agency holds no formal role in emergency coordination, it says it may assist with contracted aircraft if first responders request support.

“The organization is often called upon by first responder organizations to support Arctic search and rescue efforts through the release of contracted aircraft,” says the PCSP, but it did not say if it would participate in or facilitate a search and recovery operation to find Bhatia’s remains.

PCSP also does not address whether it has considered developing minimum field safety standards or implementing any form of external review for high-risk expeditions.

“You can’t rely on institutional memory or internal processes to manage field risk in the Arctic,” Stark says. “It needs structure. It needs training. And it needs national coordination.”

Stark, Short, and Didier all agree national standards would improve the overall safety of Arctic research missions. The PCSP appears to be the federal agency best suited to tackle the challenge, but for now, it appears to be unwilling.

“We’ve learned a lot. We’ve changed our own practices. But system-wide? I’m not sure much has changed,” says Didier.