Expert on why our understanding of cause and effect 'doesn't hold in complex systems'

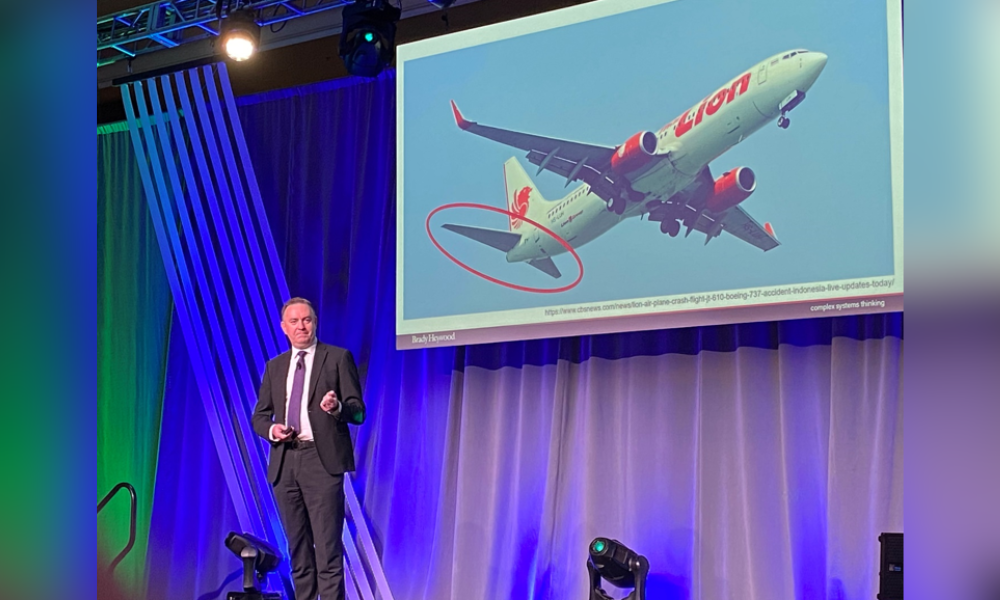

In the pristine surroundings of Banff, Alberta, at the annual Energy Safety Conference, forensic engineer Sean Brady presented a compelling analysis of catastrophic failures in complex systems. His keynote address, centered on the Boeing 737 MAX 8 tragedies, captivated a room full of health and safety professionals, providing stark lessons on the nature of cause and effect in the modern industrial landscape.

"The Boeing 737 MAX crashes illustrate that our intuitive understanding of cause and effect doesn't hold in complex systems," Brady explained. "We tend to look for linear, proportional relationships where big effects have big causes. However, in complex systems like modern aircraft, this is rarely the case."

Brady describes complex systems as interconnected components whose interactions can lead to unpredictable, emergent behaviors. This framework challenges the traditional Newtonian worldview where actions and reactions are directly correlated in magnitude and simplicity.

Using Boeing’s 737 MAX as a case study, Brady detailed how a series of seemingly minor technical and organizational missteps—each a "grain of sand"—accumulated to create a condition ripe for disaster. He described the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), initially designed to enhance flight safety, which instead became a pivotal factor in the crashes due to reliance on faulty sensors and inadequate pilot training.

"Imagine a hill of sand," Brady said, using a metaphor to clarify his point. "Each grain of sand is a decision, an action taken during the design and development of a system like the Boeing 737 MAX. Over time, these grains accumulate, building a hill. It only takes one additional grain, seemingly insignificant, to trigger an avalanche."

This analogy struck a chord with the audience, as they understood the need for safety professionals to not only focus on the apparent causes of incidents but also to understand and address the underlying systemic vulnerabilities that could precipitate a crisis.

"The real issue," Brady continued, "is not just the technological failures but also how organizational culture and processes contribute to these systemic risks. At Boeing, the shift from an engineering-driven to a cost-driven culture created a steeper hill, making the system more susceptible to failure."

The implications of Brady’s analysis extend beyond aerospace, touching every industry where complex systems play a critical role. His call to action for safety professionals is to foster an organizational culture that prioritizes a deep understanding of systemic interactions over a superficial treatment of individual failings.

"If you want to prevent large failures, start by looking at the hills, not just the grains of sand,” suggested Brady. “Our job is to manage these hills effectively, to understand and mitigate the risks before they lead to disaster."

Brady's presentation not only shed light on the critical weaknesses that led to the Boeing 737 MAX crashes but also provided a framework for thinking about and managing risks in complex systems. For the health and safety professionals gathered in Banff, it was a powerful reminder of the responsibilities they carry and the impact of their work on preventing incidents.