'Untrained and under pressure': Absence of guide falls short of global standards

“Maya made mistakes,” says Benjamin Gready, the husband of Dr. Maya Bhatia, as he speaks about the mother of his two children and the crucial moments before she was lost during a field expedition on an Arctic glacier. He believes the presence of a guide could have prevented his wife’s death. "The conditions were such that somebody at some point, untrained and under pressure, was bound to make a bad decision. An independent safety person would have been invaluable," suggests Gready.

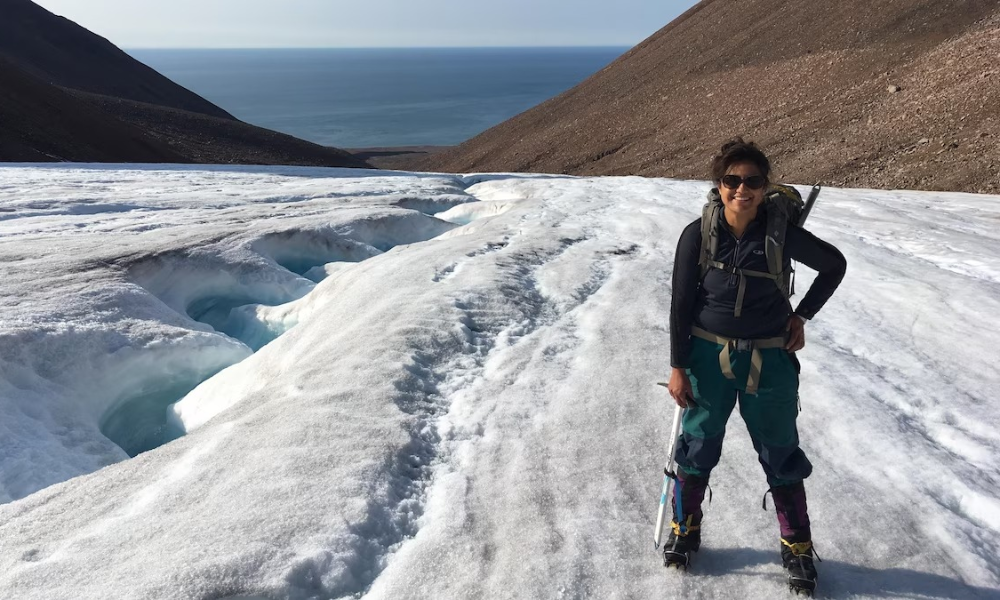

Bhatia, a world-renowned Arctic researcher, distinguished biogeochemist, and professor at the University of Alberta lost her life on August 16, 2023, while attempting to collect a water sample on the Jakeman Glacier near Grise Fiord, Nunavut. She slipped into a river and was swept over a glacial waterfall, known as a moulin. Her body has not been recovered.

Gready is also a glaciologist and knows a few things about working in harsh and unforgiving environments. He also understands the kind of pressure researchers face as part of their efforts to enhance humanity’s knowledge while maintaining sources of funding, which are largely dependent on their ability to produce results, like collecting water samples from glaciers.

"You put somebody in that sort of pressure and expect them to make the right safety decisions all the time, and it’s just unrealistic," Gready explains. He says his wife should have been wearing crampons when she rushed off a helicopter to quickly gather the water sample, a decision made in haste, because of unfavourable weather conditions, including winds so strong the helicopter pilot didn’t turn off the engine. Gready also suggests someone should have been with her traversing the glacier, tethered together using a rope.

Gready believes these fatal mistakes might have been avoided if an experienced guide had been present. "An independent safety person would have prevented this from happening in the first place," he insists.

International standards on glacier guides

In stark contrast to Canadian practices, several international organizations mandate the use of field guides for glacier research. The United States National Science Foundation (NSF) requires a field safety guide to accompany teams in hazardous environments, adjusting the guide-to-researcher ratio based on a thorough risk assessment. "We make a risk assessment of the environment, the research work plan, and the experience of the team. The most common configuration is one guide per field party, with additional guides if a research team will be splitting into smaller groups for daily activities," stated an NSF spokesperson.

Similarly, the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) employs field guides for all glaciated terrain work, usually maintaining a 1:1 or 1:2 ratio. "Field Guides are alpine mountaineers, usually from an outdoor instruction or guiding background. They undergo prolonged training and gain experience in Antarctica to equip them with the skills needed for polar travel," BAS explained in a statement.

The Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) does not have a firm requirement but strongly recommends considering guides in risk assessments.

The Canadian context

Despite being the federal agency that provides logistical support and helps facilitate Arctic research, Canada's Polar Continental Shelf Program (PCSP) does not mandate the use of mountain or field guides. Instead, researchers must create a health and safety plan approved by their institution's Occupational Health and Safety authority. This decentralized approach leaves significant gaps in ensuring consistent safety standards across research expeditions. According to a statement from the PCSP, "researchers are responsible for all aspects of the Health and Safety code, including in-field operations and ensuring all participants have the appropriate training required." But researchers are not safety experts.

Cary Ingram, chief safety officer with the Workers' Safety & Compensation Commission of the Northwest Territories & Nunavut, says the investigation into Bhatia's death did not consider the absence of a field guide as a contributing factor. "The use of guides was not one of the outcomes in our investigation," says Ingram. He also says there are no plans to make the WSCC’s investigation report public or provide it to the family.

"Having former colleagues who now work for agencies like NASA, I know the safety protocols are just so above and beyond what PCSP and the University of Alberta employ,” explains Gready. “An independent safety person, like a mountain guide, would never have let anyone go onto the glacier without proper equipment."

Lack of transparency from University of Alberta

Canadian Occupational Safety asked the University of Alberta about its health and safety policies regarding the deployment of guides during research work on glaciers. We also asked the school if it will release its investigation report publicly or provide it to the family, as it initially promised the family a full and transparent investigation.

The request was made Friday July 19th and was acknowledged the same day by a spokesperson who said, “we’ll check into this for you,” but also noted “we are experiencing a high volume of requests currently and many people are away, so things might move a bit slower than they would normally.” The school has not responded to the questions.

Moreover, Ramesh Bhatia, Maya’s father, revealed the University offered to share the investigation report only if the family agreed to a Non-disclosure Agreement (NDA). "We said no. They threw the whole kitchen sink in there. What the hell are they trying to hide?" the grieving father questions.

The tragic loss of an award-winning climate scientist underscores the critical need for stringent safety protocols in Arctic research. International standards advocate for the inclusion of field guides or mountain guides to mitigate risks, a practice not mirrored in Canadian policies. The lack of a cohesive safety mandate in Canada and the University of Alberta’s reluctance to disclose its investigation report without an NDA raises serious concerns about transparency and safety accountability. "I just don't want another family to go through what we have," pleads Gready, who hopes his wife’s death will lead to safety improvements.